When chaos threatens, what rules still make sense?

Jewish time continues. Even this week, still heartbroken by the massacre of ten beautiful souls in Buffalo New York, and now reeling from the tragedy of the massacre of nineteen children and two teachers in Uvalde Texas, it’s going to be Shabbat again.

Lately it’s Tevye, dancing despite the pain, who keeps coming to mind. Our ancestors were experts at this kind of strength – the ability to keep on keeping on, to sing in the face of sadness and celebrate Shabbat after a pogrom. But our grandparents and parents raised us as far away as they thought they could get from our needing to learn that secret of survival. Alas, the refuge they sought was fleeting. Even when they converted out of Judaism to save us, many of us still sought a way back to the identity we longed for.

This is who we are, as deracinated as we may have become. We are the Jews (and those who love them), and we have ways of holding on. The times in which we are living are those that test your grip.

On this erev Shabbat, while chaos swirls us into existential nausea, we need each other and we need to keep holding on.

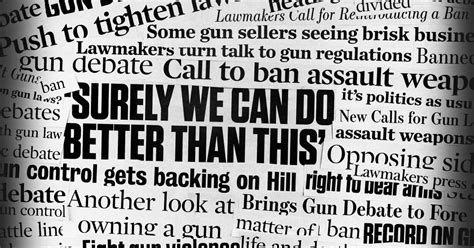

The parashat hashavua, the last one of the book of VaYikra (Leviticus) speaks to us of the insensibility of rules that we yet hold on to in order to live; the name of the parashah, BeHukotai, refers to the kind of rules – hukot – that are not necessarily amenable to reason, yet necessary. Turning to non-sense makes sense in a week when nothing makes sense, as people in elected positions prove their murderous hypocrisy by continuing to block meaningful gun control in the only country in the world in which there is a mass shooting nearly every day of the year.

We might call them House Rules, as in the old saying “House of Jacob, People of Israel” which can be understood as referring to female strength and male strength. That of women is considered more mysterious, as are the hukot.

Hukot include counting the Omer, of which we are in the 41st day on this erev Shabbat, 26 Iyar 5782, May 27 2022. A new day, one that those murdered by white supremacists in Buffalo and in Uvalde, and in so many other places, deserved to see. We get to see it; we must treasure it and use it for good as we are able.

Hukot include lighting candles tonight at sundown in honor of Shabbat, logging off social and other media for a day, and baking bread, or gardening, or doing whatever it is that nurtures your soul and the world to which you are connected. Shabbat says to us that it may not make sense to us to let the world go on without our awareness for a day, but unless we learn to practice ignorance of this sort, we will believe that our knowing about it somehow matters. In truth, we are not built for 24/7 awareness, and finding out later about things you cannot affect hurts no one, and will help you.

The world in which we live is full of madness and pain; Shabbat and the community that keeps it is an oasis of sanity and the memory of goodness. Memory is necessary to hope; once upon a time you were not afraid, you were not sad, you were not troubled. For the sake of the work we must do to heal our world, hold on to our House Rules, and let them reassure you that the Rock of our people is still in place, and you can hold on in all this terror, and we will hold each other together, and help each other to notice that there is still joy and we must, we absolutely must, feel it.